Another Case For Making Bad Art

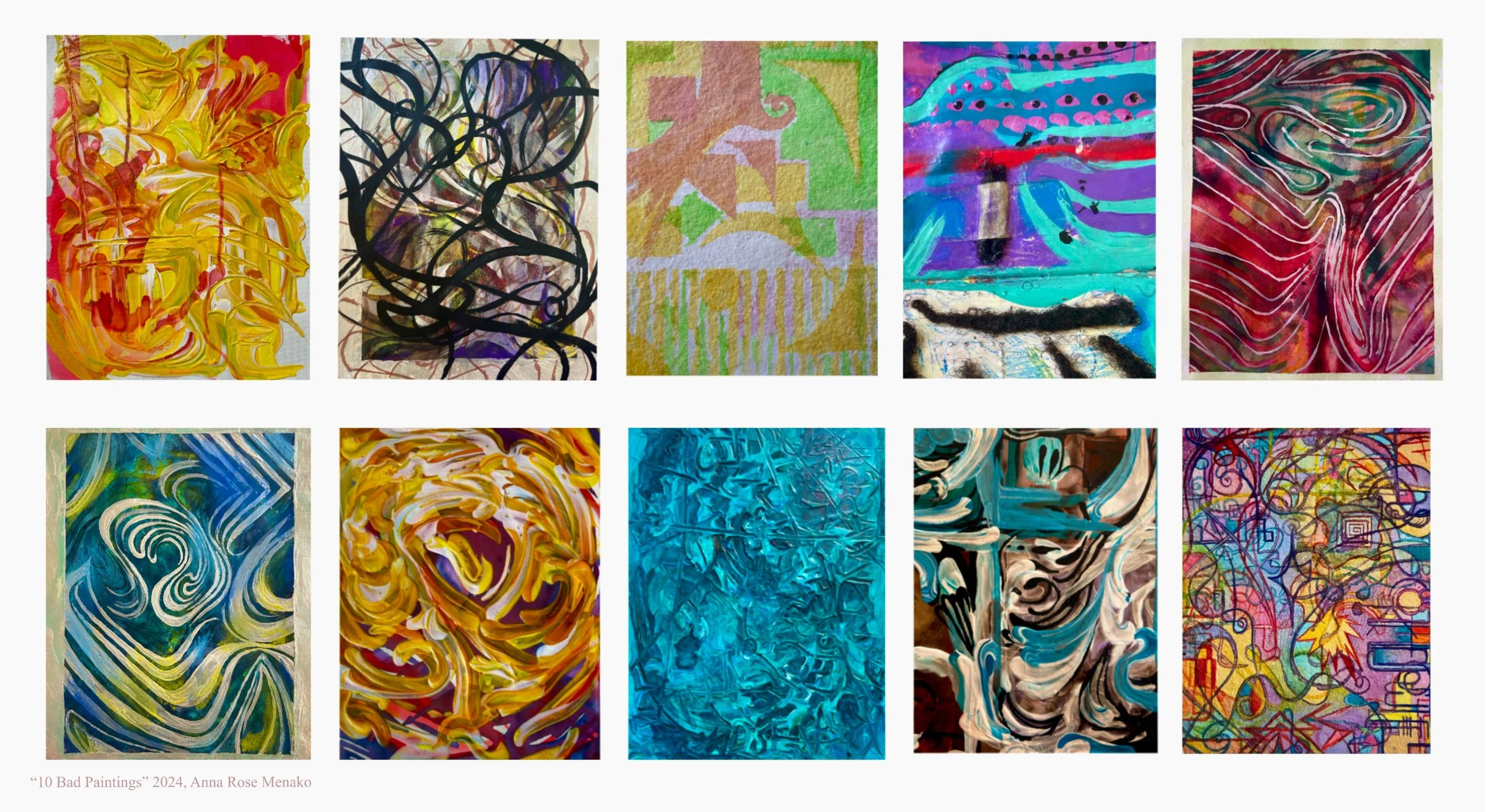

It all started with ten bad paintings.

Sometimes life gets in the way and art is deprioritized, sometimes for long stretches of time. Returning to your craft after a hiatus can feel daunting. The fear of being too rusty, too out of practice and behind. The last time I felt this way, I challenged myself to make ten bad paintings. In doing so, I found that the goal of intentionally creating “bad” work freed me from the pressure to live up to an impossible standard of perfection. It made my fear of being behind or too rusty obsolete. This process also made me examine what “ugly” or “bad” art even meant.

Challenging myself to make bad paintings led to unexpected creative breakthroughs. Each brushstroke I attempted to make “ugly” led me to realize how this perceived ugliness can balance, work in contrast with, and heighten the beauty of other elements. I found that this mirrored the depth and nuance of real life.

The idea that beauty doesn’t need to be the highest goal in art is not new. Entire creative movements have been founded on it, from grunge, to dada, to punk, and countless other anti-aesthetic genres. By contrast, artists who favor more classical and traditional techniques and styles can sometimes trade rawness for polish. This refinement can be intentional and powerful. But when it is a default habit it can risk stifling expression and setting up unnecessary creative roadblocks.

Perhaps originality is over-romanticized. What if originality was seen as something that didn’t need to be chased or aspired to, but was instead simply an inevitable by-product of the artist's hand in the creative process. Everything borrows from what came before. There is beauty and humility in acknowledging that there is nothing new under the sun, and that sometimes the most satisfying art can come from reusing common tropes, familiar imagery, and tried-and-true methods.

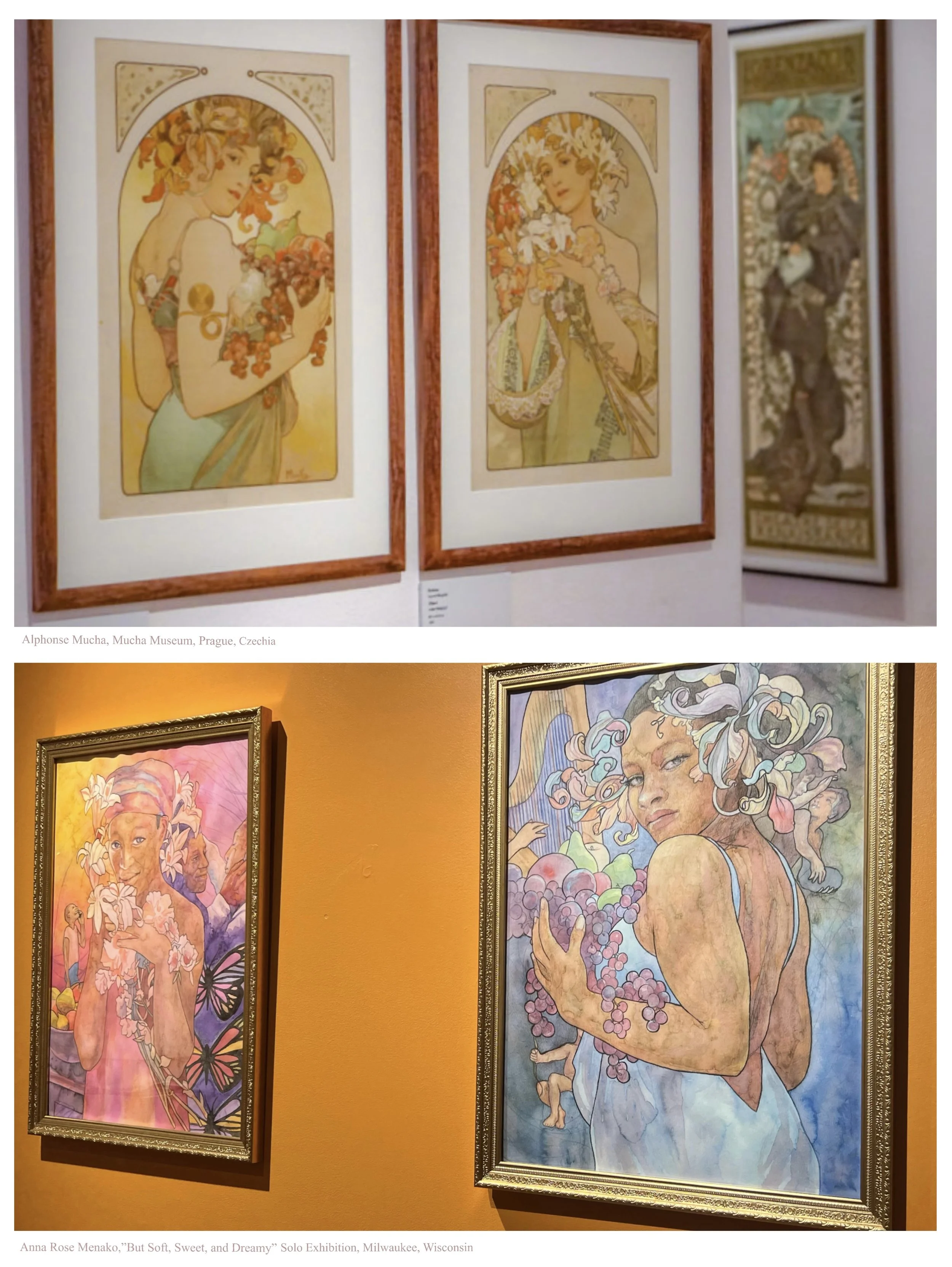

For years, I have been a shameless Alphonse Mucha copycat. When I visited the official Mucha Museum, I was almost embarrassed at how blatantly the portrayal of my “But Soft, Sweet, and Dreamy” portraits echoed Mucha’s! But I also knew that these were not copies. Instead, I emulated Mucha's work in a way that was unique to me, reinterpreting them filtered by my own sensibilities. Getting that work out of my system was less an act of mimicry and more of a launchpad that allowed me to take these aesthetic elements even further and make them truly my own.

I once heard a fellow artist say something to the effect of, “I don’t mind if other artists try to copy my style. If they have the skills to do it convincingly, then good on them.” To this day, it’s my favorite sentiment on the matter. I think when artists call other artists out with accusations of “copying their style”, due to the presence of similar elements and motifs in their work, it misses the point. Assuming copyright is respected, artists should have the freedom to emulate whatever inspires them, as closely as they may. It’s not being a copycat, it’s how culture works. And it's a flattering testament to the impact of the work that inspired them.

Artists should also credit their influences. Doing so doesn’t diminish our work, it honors the place those influences hold in the unique tapestries of our lives and practices.

That is my case for making bad art. Unoriginal art. For letting yourself be shamelessly inspired by what resonates deeply with you. Your honesty doesn’t require novelty. Sometimes, creating something imperfect or derivative is what will lead you back to your truth.